Author Archive

The Wellington Apartments

Stylistically, the Wellington is typical of multi-family dwellings found in the North Ghent neighborhood of Norfolk, VA. When the Wellington was constructed c1914, it was under S.L. Nusbaum & Co management. An ad in the Virginian-Pilot dated September 1916 described the apartment as a “luxury to live in,” “absolutely fireproof,” and features “plenty of sunshine and fresh air.” The apartment has “two tile bathrooms, porcelain tubs, tile kitchen, and tile pantry.” There is a “large living room, large dining room, sleeping porch, and three bedrooms.” Early residents of The Wellington included several businessmen in Norfolk; including Harry Levy (Philip Levy & Co. and American Home Furnishers Corporation), Nathan Hesslein (Hesslein Bros & Co), JE Humble (Stimmel Distilling Co.), and Frank Jacobs (Frank Jacobs & Bros).

In 2020, Commonwealth Preservation Group served as the tax credit consultant for the building’s new ownership. The layout of the historic plan remained intact with a few minor alterations to accommodate modern day needs. The biggest undertaking for the project was bringing the building up to current building code regulations and installing new central heat and air, as well as updating electrical systems. Modern finishes were removed revealing the historic hardwood floors. Once considered a “luxury to live in” has once again returned to its former glory.

The Cavalier Hotel, Virginia Beach, VA

The idea of the “Grande Dame of the Shore” took hold decades prior to the Cavalier Hotel’s construction, following a 1907 fire that destroyed Virginia Beach’s most prominent resort. In the 1920s, as a rail line was extended out to the city and commercial and residential development began to alter the landscape, the Virginia Beach Resort and Hotel Corporation was formed to make the resort a reality. The regionally prominent and prolific architectural firm of Neff & Thompson designed the Cavalier, incorporating commercial space for tourists to shop on site and providing for all of the latest modern amenities. The 200 guest rooms at the Cavalier, each twelve by twelve feet, possessed hot water, cold water, sea water, and ice water spigots. On opening day, the Cavalier was toured by over 7,000 people. The hotel was the biggest news in Tidewater in a generation. Official celebrations lasted a week, and one event included daylight fireworks depicting life-sized cavaliers on horseback. Almost immediately, Virginia Beach’s premier hotel began to attract high society vacationers. The Who’s who list of famous visitors includes 9 U.S. presidents, First lady Edith Bolling Galt (a regular visitor), and Eleanor Roosevelt, who came with the Girl Scouts. Celebrity clientele included Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, Betty Grable, Jean Harlow, Bette Davis, and F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Vacationers enjoyed leisure activities such as daily or weekly concerts, plays, horseback riding, golf, miniature golf, shooting, hunting, archery, tennis, and boating. A turning point in the building’s history occurred in 1942, when the Cavalier was annexed by the Navy for use as a radar school.  Three years later, when the hotel was returned to its owner, the building was badly in need of restoration. A subsequent series of renovations occurred between the 1940s up through the early 2000s; the interior layout of the guest rooms was heavily altered, with most rooms expanded outside of their original, small footprints. The public spaces of the Cavalier, however, remain largely intact. Especially notable are the building’s Rotunda Lobby, the Raleigh Room (the lounge) and Pocahontas Room (the dining room), which retain much of their original detailing, including plaster walls, historic doors and transoms, and the terrazzo floor in the Raleigh room. The hotel’s lovely salt water pool and sunlit loggias also remain intact. The Cavalier Hotel was found significant at the local level for its architecture and its role in social history as one of Virginia’s preeminent resorts. The building has recently changed ownership and will be fully restored as a functioning hotel. The Cavalier is currently the subject of an ongoing, historic rehabilitation tax credit renovation.

Three years later, when the hotel was returned to its owner, the building was badly in need of restoration. A subsequent series of renovations occurred between the 1940s up through the early 2000s; the interior layout of the guest rooms was heavily altered, with most rooms expanded outside of their original, small footprints. The public spaces of the Cavalier, however, remain largely intact. Especially notable are the building’s Rotunda Lobby, the Raleigh Room (the lounge) and Pocahontas Room (the dining room), which retain much of their original detailing, including plaster walls, historic doors and transoms, and the terrazzo floor in the Raleigh room. The hotel’s lovely salt water pool and sunlit loggias also remain intact. The Cavalier Hotel was found significant at the local level for its architecture and its role in social history as one of Virginia’s preeminent resorts. The building has recently changed ownership and will be fully restored as a functioning hotel. The Cavalier is currently the subject of an ongoing, historic rehabilitation tax credit renovation.

345 S. Church Street, Smithfield, VA

345 S. Church Street is a 1902 Colonial Revival Style house, 3 stories in height and displaying high style, classical detailing. Its full width porch possesses detailed, fluted columns and is two stories tall at its central bay. In its interior, the house is characterized by intact, tiled Victorian fireplaces, decorative plaster ceilings, and a third floor that was traditionally a ballroom. The dwelling, which retains much of its ornate original detailing, is a typical example of the grandeur found throughout the Smithfield Historic District.

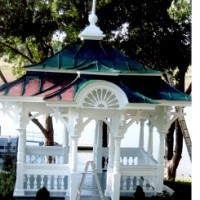

When new owners purchased the home, they set about remediating issues of deferred maintenance that had compromised some of the building’s historic material. In particular, decorative plaster ceilings were displaying water damage due to leaks; these were mended in kind to restore their original detailing. Prior owners had removed the dwelling’s historic slate roof in favor of modern asphalt shingle, which was in fair condition at the outset of this renovation. New ownership replaced the roof in kind. A 1985 kitchen expansion had resulted in the enclosure of an historic rear porch. As a result of this project, a new rear porch was added onto the back of the dwelling, to replicate the original condition. An historic, 1920s garage was converted to an office, and its modern carriage door was replaced with a contemporary compatible door more in keeping with the historic design of the outbuilding. A waterfront gazebo, either original to the home or predating the dwelling, was also fully restored.

Auto Row Historic District, Norfolk, VA

The growth of Norfolk’s Auto Row Historic District is closely tied to the rise of the city’s automobile industry. Although the area was initially founded as a lower and middle class neighborhood, most the residential buildings were demolished in the early 20th century to make way for Norfolk’s growing commerce. Conveniently located between several of Norfolk’s main thoroughfares (Granby Street, Monticello Avenue, and Brambleton Avenue), most of the new buildings were constructed as dealerships, repair shops, parts, suppliers, and even small light industrial manufacturers all feeding one common source: the car. As an example of how important the automobile was to the growth of the district, every parcel in the 700 block of Granby at one time or another contained a business related to the auto industry. The unprecedented commercial growth in this district turned Granby Street into a major vein of the city, with parcels commanding so-called “fancy” prices.

Most of the buildings in the district are industrial style, one or two stories in height. Popular styles include Moderne, Stripped Classical, International, Art Deco, and variations on purpose-built Commercial Buildings. Many buildings possess large windows meant to maximize auto display. One of the district’s important resources is the Texaco Building, constructed in 1918. A bastion of Norfolk’s auto industry, the building, with its signature star stone detailing, began as a service station and eventually became the company’s regional headquarters. The Golden Triangle and the Harrison Opera House serve as important examples of district expansion outside of the auto industry. At the time of its construction in 1961, the Golden Triangle was the first major hotel constructed in 50 years, and the only major hotel located outside of the traditional downtown area. The Harrison Opera House, an International/Moderne style limestone building constructed in 1944, served as Norfolk’s primary entertainment venue until Chrysler Hall and Scope were erected in the 1970s. The building’s east elevation is historic.

The Auto Row Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in August of 2014.

212 Bay Avenue, Cape Charles, VA

Cape Charles sprang into being in the late 19th century. The brainchild of two northerners, the township was intended to be the final stop on the railroad tracks leading from New York and Philadelphia. The settlement was laid out in a unique manner, with a square park serving as the center of the town upon which four main streets converged. At the outset of the 20th century, Cape Charles thrived due to the bustling railroads; however, in 1958 passenger trains quit Cape Charles entirely, and visits from freight trains slowed. Since that time, the seaside town has remained relatively unchanged, retaining much of its historic character and charm.

212 Bay Avenue is a brick, Colonial Revival style dwelling overlooking the bay where freight ships once ferried railroad cargo to Norfolk. The dwelling, which has a distinctive five bay front porch, has been renovated for use as a bed and breakfast. As a result of the tax credit project, the kitchen and bathrooms underwent renovations and HVAC was installed. Windows were repaired and the exterior brick walls repointed wherever deterioration was detected. Plaster throughout the dwelling was restored. The home’s original garage had been altered sometime in the past, with two manual garage doors inserted as well as a non-original pedestrian door. In order to accommodate modern cars, a new, automatic garage door was installed. Moderate landscaping was done as well, with permeable clamshell parking poured to accommodate guests.

Powell-Ablard House, Alexandria, VA

The Powell-Ablard house is a c1840 brick dwelling within the Alexandria Historic District, located on a fairly large urban lot. In 2010-11, a series of violent ice storms caused structural damage to the house. Snow-laden branches yanked power cords from the walls, and a large ice dam caused the dwelling’s brick veneer to delaminate from the structural façade. To address these weather-related issues, a structural engineer inserted tie rods within the floors at the dwelling’s second and third levels, to stabilize the exterior walls. After it was discovered that a 1989 renovation had replaced most of the historic mortar with Portland cement, brick was thoroughly examined for signs of weakness attributable to mortar strength. Repointing was accomplished as necessary. On the building’s southern elevation, a deteriorated wood frame pergola was removed to make way for a sunroom addition. According to Sanborn maps, this new room is located at the site of a vanished three-story addition, which had been installed when the dwelling housed multiple families. The project scope also included systems updates and interior maintenance such as plaster repair.

Although this application was filed largely after the fact, as the owner was unaware of Virginia’s rehabilitation program at the outset of the renovation, the completed work qualified for tax credits.

Virginia Ice & Freezing Corporation Warehouse, Norfolk, VA

In the early twentieth century, Norfolk was one of the largest producers and distributors of oysters and fish in the country. Local ice and cold storage facilities served as vital support to this industry. The Virginia Ice & Freezing Corporation, est. 1920, had one of the largest ice and storage operations in Norfolk. Its warehouse, located along the narrows of the Elizabeth River, was likely designed by notable Norfolk architect B.F. Mitchell.

A three-section concrete block building, today it represents the best-preserved cold storage warehouse in the City of Norfolk. Operated for many years by Krisp-Pak, the building once had this logo brightly emblazoned across its second level. The warehouse was found significant under Criterion A of the National Register of Historic Places, owing to the important role it played in the seafood industry vital to Norfolk’s economy since colonial times. Due to the building’s well-preserved 20th c. Commercial architecture, it was recognized a second time under Criterion C.

Commonwealth Preservation Group nominated the Krisp-Pak building to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. The following year, CPG served as tax credit consultant for the building’s renovation. New ownership decided to divide the warehouse into 71 residential units. Floor plan changes included a rooftop addition and the introduction of two light wells to provide sunlight to the warehouse’s interior section. Updated electrical and HVAC systems made the residences habitable. The final result, the Riverview Lofts, retains its industrial appearance, preserving a remarkable building that may have otherwise fallen into disuse and disrepair.

Talley House, Norfolk, VA

The lovely Talley House was built in 1905 in Norfolk, VA. Present on every elevation of the home, beautiful, historic diamond pane windows offer striking views of the Lafayette River. A breezy wraparound porch offers shelter during humid summers and provides up-close views of the setting sun.

When a new family purchased the home, they needed to construct additional living space but wanted to preserve Talley House’s historic character. CPG helped these clients apply for tax credits on the rehabilitation of the historic structure and advised them on the appropriate construction of a new addition, one that would complement the dwelling’s historic fabric.

Although the project is still ongoing, the first phase of work was completed in 2013. Plumbing, electrical, and HVAC upgrades have been installed and a new roof shields the dwelling and its expansive porch. Wood floors throughout the home have been refinished. The building’s new addition is attached at its rear, leaving the façade intact. The expansion is a contemporary compatible companion to the home’s historic footprint—in keeping with the home’s style, yet easily identifiable from the original fabric.

409-411 Dinwiddie Street, Portsmouth, VA

409-411 Dinwiddie Street is a c1910 Victorian house with a wide front porch, located in the Old Towne Portsmouth Historic District. The home was originally built as a townhouse style duplex, but became a fourplex post-1950s. The current owner bought it while renovations were in medias res and completed the project in a manner respectful of the building’s architectural history. The wood clapboard siding was retained, as was the historic metal roof overtop of the front porch. A previous owner had inserted two modern windows underneath the roof gable at the third floor; the current owner removed these and inserted a single window to replicate the building’s historic appearance. All historic woodwork throughout the home was retained.

As the owner of 409-411 Dinwiddie Street was unaware of the tax credit program at the outset of the project, CPG filed a retroactive application for state and federal tax credits.

304-308 E. Bank St. (Colonial Marble), Petersburg, VA

This c.1890 warehouse was used by the Barnhart Mercantile Company as a showroom and manufacturing facility for cultured marble bathroom and kitchen products. After the business relocated, the structure underwent a conversion into an 85-unit rental residential building. The warehouse’s interior was divided into apartments incorporating many of the building’s industrial features, such as exposed brick walls, beams, and pipes. In order to meet sound and fire code requirements, workers applied dry wall to the building’s wooden ceilings; this treatment is reversible and does not harm the historic wood underneath.

The building’s original exterior was reestablished by removing modern additions and a loading dock. At the conclusion of the project, the building maintains an appearance similar to that which it displayed in the 1890s, even so far as the historic, hand-painted signs identifying it as the headquarters of the Barnhart Mercantile Company.

7 E. Jackson Street, Richmond, VA

7 E. Jackson Street sits near the heart of the Jackson Ward Historic District, in an industrial section. A number of businesses have occupied the 1920s warehouse throughout its existence; the building once served as a wood shop, a shirt factory, a warehouse, and a bakery/drugstore, all within the first few decades of its life. Most recently, it cycled between serving a storage facility and sitting vacant. As the building fell further into disuse, graffiti appeared on its exterior. Vines and excess, unused conduit began to clutter the painted brick walls.

In 2012, a developer initiated a tax credit project to revitalize the aging warehouse. In order to insert 8 functional apartments within the historic space, skylights were inserted for the second floor units; these remain hidden behind the building’s parapet and provide light without altering the exterior appearance. Within the building, historic treatments were painstakingly preserved, and as a result, many apartments possess unique character defining features. In one unit, historic lift mechanisms remain appended to the ceiling. The building’s laminated concrete floors were carefully maintained throughout, meaning that the floors in many apartment possess original swirls and historic patches. The closet in another unit was once a rear staircase—the first few steps remain, providing unique access to the inhabitant’s clothes. This hidden feature will only be appreciated by a few individuals, but further shows the project’s dedication to honoring the warehouse’s architectural history.

The Palace Theater, Cape Charles, VA

Ingrid Bergman was one of the first fair faces to grace the silver screen at the Cape Charles Palace Theater. Today, the former movie house turned live arts performance hall houses Arts Enter, a non-profit organization that promotes theater, dance, music, and the visual arts. Arts Enter first began work on the historic building over a decade ago. The restoration has been a thoughtful one: the building’s two historic murals were completely refurbished, the stage was slightly expanded to allow for greater movement, and disintegrating theater seats were replaced with wider chairs for a modern audience. An art gallery was established in the front of the building and a dance studio installed upstairs.

The theater retains many of its eye-catching Art-Deco features, such as a set of double leaf doors with bubble-like circular panes. Thankfully, these were in good condition at the outset of the project. Other items required serious repairs. One of the major thrusts of the renovation included replacing the building’s disintegrating marquee, which was in such poor structural condition that it could not be saved. Over previous decades, the feature had been mended so many times that little historic material remained. The ticket window near the building’s entrance also received new glass, as former panes were broken.

CPG received the final tax credit approval on the Palace Theater in 2013. However, the building may restart renovations sometime in the future, as Arts Enter continues to expand on their mission of bringing first class arts to the town of Cape Charles.

2601 Granby Street, Norfolk, VA

2601 Granby Street, a building well known by sight in the Park Place Historic District, was nearly destroyed by fire in 1997. Thanks to a previous owner, the building was restored rather than condemned. When a new owner purchased the dwelling in 2011, much of the interior rescue had been accomplished, but exterior maintenance barely had been addressed. In addition, a 1909 carriage house that predated the main structure was not yet renovated. Previously gutted, the building had damaged doors from a combination of neglect and burglaries attempted during the period following the fire, when the property sat vacant. As part of the project, damaged exterior woodwork on the main building was carefully repaired and the historic slate roof mended. The porch floors, comprised of decorative tiles arranged in a flower pattern, were gently restored.

The most drastic work concerned the carriage house, which, at the outset of the project, had damaged windows, deteriorated doors, and the ghosted outlines of two apartment units. The building’s current owner took on the remaining apartment construction and the necessary maintenance updates. As the carriage house was historically unfinished, brick walls were left exposed on the interior, lending the building an industrial feeling. The damaged garage door, which was literally falling apart, was replaced to match. The remnants of the historic door now adorn the walls of the second floor apartment as a reminder of the dwelling’s former condition.

Chatham Elementary School, Chatham, VA

Chatham Elementary School is a massive, Colonial Revival Style building constructed in 1925. The structure was expanded in 1964, resulting in over 27,000 square feet of space, which fell into disuse after the construction of a modern school. The building lay vacant until 2012, when a developer initiated a large scale renovation project and contacted CPG to serve as tax credit consultants.

Today, the former elementary school has been converted in senior apartments. The historic slate roof, which had been edging toward disrepair, was completely restored. Existing windows were kept and mended, further maintaining the building’s historic integrity. Features unique to the building were showcased: classroom cabinets, once used for schoolbooks and supplies, will now be used as storage within new apartments, and wherever possible, old blackboards remain upon the walls. Each new apartment was carefully configured within an individual classroom.

The state and federal tax credit programs help incentivize the rescue of unused historic buildings like Chatham Elementary. The former school now once again provides a tangible community benefit.

Navy Y, Portsmouth, VA

517 King Street was originally constructed in 1916 as a school for a local church. Later, the building was used as the Portsmouth Navy Y, and in 2013, it was converted into apartments.

When CPG was contacted to serve as the project’s tax credit consultant, the former Navy Y was empty and deteriorating. Gaping holes in the roof had caused substantial water damage, especially to the structure’s upper floor. The building required not only a roof replacement and new drywall, but also updated plumbing and electric systems. Modern partitions had subdivided former classroom space; these divisions were removed, and new partitions configured within historic walls. Almost one hundred years later, each former classroom is now an individual apartment.

The picture at the left is of the Navy Y’s stairs, coated with rust at the outset of the project. The picture at the right shows these stairs after the building’s complete renovation.

Surry County Visitor’s Center Analysis

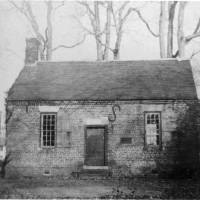

When local officials decided to convert the old Surry County Clerk’s Office to the area’s Visitor’s Center, CPG was consulted to provide guidance on the treatment of this historic property. Constructed c.1825, the small brick building sits adjacent to the county courthouse and is believed to one of only six antebellum buildings in the town of Surry. A site visit confirmed the building’s progressive state of disrepair, including damage from previous renovation work. Pooling water had also caused the structure to settle and some of its mortar to deteriorate. CPG’s assessment outlined the building’s most critical restoration needs and recommended further consultation with experts such as archaeologists and restoration masons to ensure the structure’s long-term viability.

Community Bank, Petersburg, VA

Prior to a 2011 renovation, Petersburg’s Community Bank had suffered from deferred maintenance with few tenants in the recent past. The owner proposed rehabilitation for mixed use, installing office space on the building’s first floor and residential apartments on the upper levels.

Constructed c.1911-1914, Community Bank is one of a few turn-of-the-century high-rise buildings in downtown Petersburg. The building is a seven-story American bond brick structure. Using old photographs, workers were able to identify and reveal historic limestone arches from under the cracked stucco covering part of the building’s exterior. The structure’s missing cornice and outer double leaf doors were also replaced. In the interior, an effort was made to preserve the building’s unique historical features. Renovations revealed closed transoms and opened up historic decorative ceilings, formerly encased in dropped acoustical tile.

Sacred Heart, Norfolk, VA

Sacred Heart Catholic Church has been a landmark of urban Ghent since its construction in 1923, completing its most recent renovation in 2011. A minor expansion remained in keeping with the Italian Renaissance style of the church, and plumbing and electrical wires were updated as needed. Some aging or damaged historical features, such as windows, brick, and roof tiles, also required restoration, and the church’s kitchen was reconfigured within its own footprint to adhere to the historic floor plan. At the conclusion of a project spanning eight years, Sacred Heart Catholic Church remains one of North Ghent’s historic community treasures.

Petersburg Old Town Historic District, 2012 Boundary Increase

The Petersburg Old Town Historic District first received recognition on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The original district encompassed most of the early portion of the city. Notable structures included groupings of 19th century warehouses, factories, and some residential buildings. In 2008, a boundary increase added a few large commercial/industrial buildings falling within the original period of significance, from the eighteenth century to 1930.

The district’s most recent boundary increase, in 2012, includes buildings entirely commercial in nature. The structures occupy one of the oldest parts of the city, but represent the area’s transition to more modern commercial use. The expansion, approximately seven acres, includes five commercial buildings erected between 1925 and 1953 and six commercial warehouses built between 1914 and 1957. The area’s period of significance now extends to 1958.

The contributing resources are primarily of cinderblock masonry construction. The district expansion qualifies for the National Register’s Criterion C, Architecture, as containing good representations of mid-twentieth century commercial/light industrial construction. The resources in the 2012 district expansion also serve as physical representations of Petersburg’s industrial past, further qualifying the expansion under Criterion A.

St. Luke’s Church, Smithfield, VA

St. Luke’s Church in Smithfield, Virginia, is the oldest remaining church of English foundation in the United States. Originally constructed in 1632, the brick building, with a single nave Gothic sanctuary and a monumental tower, has been modified over time. Later additions include the insertion of Jacobian inspired interior finishes and late nineteenth century stained glass windows.

The structure underwent renovations c.1890 and from 1953-1957, but despite ongoing maintenance and a dedicated foundation, by the early 2000s the building was again in disrepair. CPG aided Historic St. Luke’s Restoration, Inc. in attaining tax credits for this most recent restoration.

In the sanctuary, deteriorating windowsills were mended and new breathable, protective panels placed on the stained glass windows. A new application of plaster matched that of the original building; plaster from the 1950s renovation had used a faux antique finish inconsistent with historically accurate limewash. Outside, an archaeologist hand-dug a new trench for pipes, guiding water away from the historic building. The restoration was planned and completed over a period of seven years (2004-2011), and the final result preserves the building’s developmental history.

Blackstone Lofts, Blackstone, VA

One of the most striking elements of the former Plantation Tobacco Company Warehouse is its stepped parapet, concealing a front gable roof with metal clad cornice. Constructed in 1909, the Commercial style warehouse was once a Tobacco Prizery and Reordering Plant. A 2010 renovation restored the deteriorating structure, refitting the factory interior with 25 luxury lofts. Workers repaired and replaced damaged roof and aging bricks, as well as reinstalled window sashes to match a single historical example found in the building’s storage. The newly renovated building remains a mainstay of Blackstone Historic District, as the project preserved both the structure’s industrial character and its arresting façade.

Seaboard/Wainwright Building, Norfolk, VA

Erected in 1926, the Seaboard Air Line Railway Building remains Norfolk’s only large-scale commercial example of the late Gothic Revival style. The nine-story building was one of the most important commissions of the regionally prominent firm of Neff and Thompson.

When first constructed, at 92,000 square feet the Seaboard Building contained the most office space of any structure in Norfolk. A reinforced skyscraper, at the time of construction it was also the third tallest building in the city. The building has an unusual V-shape and a largely intact exterior. The lobby retains most of its notable Gothic Revival decorative details.

Previous tenants also render the building significant. Founded in 1832, the Seaboard Air Line Railway was a major player in the east coast market, and consisted of nineteen railroads prior to the Great Depression. The company moved both passengers and freight along the coast. Prior to WWII, however, the Seaboard Air Line Railway relocated and the Wainwright Realty Corporation occupied the Seaboard Building. The word “Wainwright” remains emblazoned in the historic limestone façade above the decorative heraldic entry arch.

The building is eligible under Criterion C for Architecture as an excellent and rare example of large-scale non-religious Gothic Revival architecture in the City of Norfolk. It is also eligible under Criterion A for Commerce as the purpose built headquarters for the Seaboard Air Line Railway.

CPG wrote the register nomination for the Seaboard/Wainwright Building and also handled the tax credit application for its most recent renovation. Formerly doctors’ offices, the updated Wainwright Building now houses popular downtown apartments. While historic features were carefully preserved, modern amenities were also added. The building also possesses a small rooftop addition, barely visible from the street, which provides residents with access to a dog run, a clubhouse space, and far-reaching views of the Norfolk harbor

117 S. Lee St., Alexandria, VA

The Alexandria Historic District achieved designation as a National Historic Landmark District in 1946, only the third neighborhood to gain this distinction at the time. Overlooking the Potomac River and Washington D.C., the neighborhood contains a number of Federal structures, as well as other architectural styles from the 18th and 19th centuries.

117 S. Lee St., a brick dwelling constructed in 1870, had a crumbling foundation and poor drainage, allowing water to seep into the basement. To remedy the problem, a structural engineer oversaw the digging out and reinforcing of the foundation. Further exterior renovations included replacing inappropriate, modern mortar with mortar specially matched to the original blend. Mid-twentieth century front steps were replaced with stone stairs oriented toward the street, replicating the design original to the house. Interior updates took into account the owner’s needs while preserving the house’s unique architectural features.

Hayden High School, Franklin, VA

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources found Hayden High School significant under Criterion A, as being associated with events that have made a significant contribution to broad patterns of history. From 1953-1970, the school served as an important site in the fight over both equalization and desegregation, issues hotly debated throughout Virginia and the United States.

Constructed in 1953, Hayden High School is a masonry building with five-course American bond brickwork, minimally adorned in a vernacular style. The school was named for Della I. Hayden, a Hampton Institute graduate who had been local leader in African American education.

In the early 1950s, during the time of the planning and construction of Hayden High School, the debate over school segregation intensified in Franklin, the Southampton County school system, Virginia, and across the nation. Although the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education provided the final word on school desegregation, the Southampton County educational system continued to resist compliance. It would be 1970 before Franklin schools were completely integrated, long after most of the rest of the nation.

As a result of integration, Hayden High School became Franklin’s Junior High. The building later closed in the 1980s and has remained vacant since that time. But, during its period as an all black high school, the building represented a focal point in the fight over segregation in the state of Virginia.